Traveling the Pennsylvania Turnpike (Interstate Highway 76) can be an interesting experience. Depending on the time of year “Penns Woods” turns its colors from the steel gray of winter to the green of summer to the brilliant contrasts of autumn. All of this is contextually enhanced by the physical nature of mountains, ridges and valleys. The present day routes of concrete, macadam and steel now replace Indian paths and the old Forbes Road that also crossed southern Pennsylvania centuries ago. Bedford County, the featured county in this week’s blog is the halfway point along the Turnpike between Harrisburg and Pittsburgh. Historically, it is perhaps best known as the location of Fort Bedford, an important 18th century French and Indian War Period military fort built and garrisoned by British troops under the command of Colonel Henry Bouquet.

Map of Fort Bedford

Although the footprint of Fort Bedford has not been traced archaeologically, historical documents and detailed journals suggest the fort site is near the Fort Bedford Museum on Bedford’s north side. The fort itself, a 21,000 square foot pentagon- shaped structure of chinked logs with a pentagon-shaped bastion at each corner supported swivel cannons. The stockade had three gates and elevated V-shaped redoubts on two sides for added defense. The fort that overlooked the Juniata’s Raystown Branch was of classic military design and typical of the period when British forts were being built on the early American frontier.

Excavation Map of Palisade Wall

Keyser Rim Sherd

Late Woodland Triangular Points

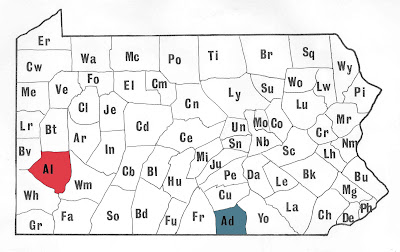

Discovery of a Keyser village in Bedford County was quite exciting and extends the range of known Keyser occupations into the Upper Juniata drainage, a region that traditionally was the territory of the Clemson Island culture at that time. A number of other Keyser Culture occupations have since been identified in the Potomac’s Conococheague and Antietam drainages of Franklin and Adams counties, however, they appear to date several centuries later in time than the 36BD90 occupation. Further afield, in the counties of York and Lancaster, Keyser pottery has been linked with 15th century Shenks Ferry Tradition village occupations and suggests that Keyser people interacted with outside groups on a level of interaction that was perhaps focused on the exchange of goods and/or the exchange of mates, economic and social strategy that served to strengthen alliances between the two cultures.

Another site was excavated by Penn State University and Juniata College in 1967 as a joint field school. The Workman Site (36Bd36) was a multi-component site predominately Late Woodland with post molds and pit features suggesting multiple house patterns. Variation in house patterns and pottery types suggest influence from the Susquehanna and Potomac Valley implying repeated reuse of the site. Pottery recovered from the excavation included Clemson’s Island and Montgomery/Page wares indicative of the earlier part of the Late Woodland approximately 900-1200 A.D.

Turning to Environmental Review and Compliance projects for Bedford County, to date there are eleven collections that have been placed in the permanent collection. The collections include prehistoric and historic period objects from archaeological investigations. Site documentation and other collection records that have been accessioned under State and Federal mandates can be accessed by arrangement with the Section of Archaeology, The State Museum of Pennsylvania.

For more information, visit PAarchaeology.state.pa.us or the Hall of Anthropology and Archaeology at The State Museum of Pennsylvania .